Fula-Fula I - Minchí

By William Anderton-Pithers

Minchí and bacalhau (image via Wikimedia Commons).

“Fula-Fula” is an ongoing exploration by columnist William Anderton-Pithers into the enduring legacy of lusophone culture in Asia, with cuisine acting as his narrative hook. Delving into the history of Portuguese presence within these regions, Will writes on the centuries' long contact between East and West and how such contact has given rise to hybrid cultures that remain relevant in an increasingly globalised world.

Minchí. What does this word mean to you? For the vast majority of readers, it probably means very little, but for anyone from Macau, a special administrative region in the People’s Republic of China, this one word probably encapsulates a feeling of home - of identity. Though it is a dish primarily based upon the same key ingredients - fried mine, potatoes, rice, and maybe even a fried egg - the dish is known across the city and each household is said to have its own take on this classic comfort food. Yet, much like the very people who adore it, Minchí has a layered and complicated history, one which combines aspects of culture from both China and the West and goes beyond the surface level of imported foods and flavourings used in an Asian culinary context. The name itself is emblematic of this fusion: though created within a Portuguese colony, Minchí is believed to be derived from the Cantonese pronunciation of the English word “minced”, reflecting yet another aspect of Macau’s history - that of its relationship with Hong Kong.

From 1557 until 1999, Macau was under Portuguese administration after diplomatic relations with the Ming dynasty had permitted them to build a trade port in the Pearl River delta. However, said agreement came with stipulations, namely the insistence that the Portuguese would pay an annual rent to China for the land it was using and that the territory, along with all its Chinese subjects, were still under China’s authority. The agreement stayed as such until 1842, in which the Treaty of Nanking was signed between the British and the Qing dynasty. This treaty brought an official end to the First Opium War between the two nations that had seen China suffer military defeat; its terms were to have a great impact on Macau’s future. Alongside China needing to pay an indemnity to the British (essentially a compensation for damages caused during the conflict) and the opening of five Treaty Ports in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Ningbo, Fuzhou, and Xianmen (which ended the tight grasp the Qing dynasty had over trade with Europe), it was also forced to cede the island of Hong Kong to the British, making it a sovereign territory of the British Empire. After this, the monopoly that Macau had once had as a major regional trading centre was truly diminished as larger ships were drawn to the deep-water port of Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour.

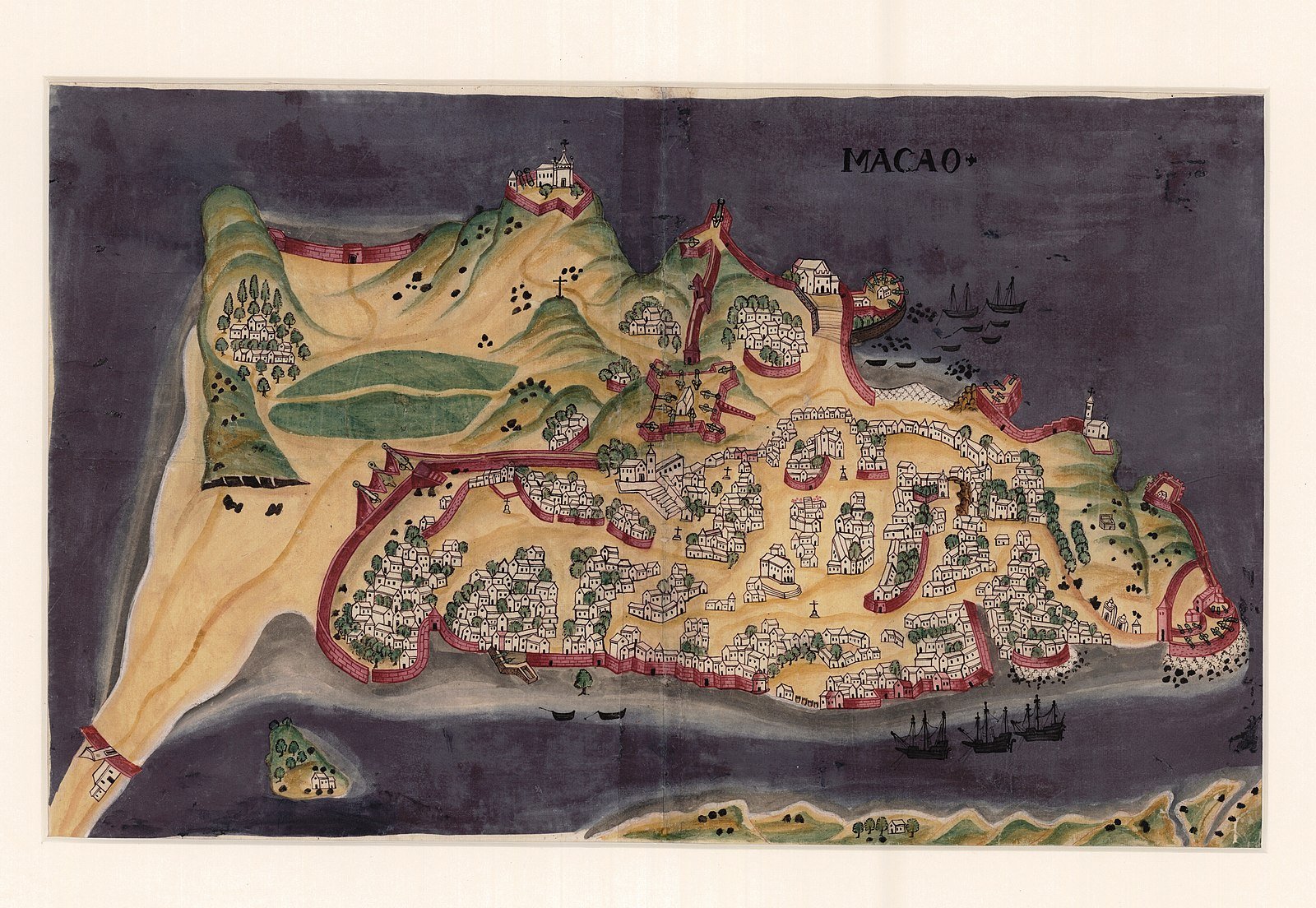

Portuguese map of Macau dating from 1635 (image via Wikimedia Commons).

In reaction to this, Portugal saw a need to further establish its own authority over Macau and in 1846, it sent naval veteran João Maria Ferreira do Amaral to serve as its governor. Almost immediately he unilaterally declared Macau a Portuguese colony and stopped paying annual rent payments to China. In addition, he imposed a new series of taxes onto the residents of Macau who had until that point been regarded as Chinese citizens, and began occupation efforts of lesser Taipa - a region that previously had not been under Portuguese control. What became quickly apparent was the discontent of Macau’s new citizens towards this exertion of foreign authority. This came to a head in the Revolt of Faitiões of the same year, with junkers on the Pearl River leading an armed rebellion against the Portuguese - something which was only subdued by Amaral’s threat of extreme violence against them if they continued resistance. Clearly a hated figure, it comes as no surprise that Amaral would later be assassinated in 1849. This, however, left the administration of Macau in a weakened state, under which China, in an effort to retake control, launched an attack against the Portuguese on the 25th August. Despite being massively outnumbered, the Portuguese were able to hold out against the Chinese troops and this event is often seen as a milestone in the assertion of Portuguese sovereignty over Macau’s territory.

And so Portugal kept control of Macau as a part of its empire until 1999, where it officially handed over sovereignty back to China after 442 years of Portuguese presence in Macau in an evening containing dragon dances and lion dances, attended by representatives from both East and West. Which brings us to today: Macau (like Hong Kong) is administered under the “one-nation, two-systems” agreement by the People’s Republic of China, meaning it has a separate legal, economic, and legislative system to the mainland, which allows it to function as a separate entity in international settings. This in turn has meant it has remained linked to the wider lusophone world.

Whilst this agreement is set to expire in 2049, the lasting impact of Portuguese presence will remain, beyond the deep-fried potatoes and aromatic chillies of Minchí which the Portuguese had brought with them centuries ago. Macau’s old town preserves the original flare of the city, with Baroque churches and traditional Chinese temples intermingling and now encased by skyscrapers and casino complexes. The Festival da Lusofonia has also been a staple of Macau’s culture since 1998, where various lusophone communities are invited to display their culture in the form of food, performances and games in order to celebrate the legacy of Portuguese influence. Though many fear the loss of this way of life within Macau, it is evident that the city itself is making concerted efforts to keep its memory alive.