Bas(qu)ing in Difference: the Beauty of the Basque Identity I: The Enigma of Euskera

The Basque Country (Photo: Via Pixabay: Kiosko)

Europe is full of culture. Yet, there is no culture quite like that of the Basques. From their intense patriotism and choral tradition to their eight surnames and enigmatic language, the Basques have, over history, fought so hard to preserve such a rich history of tradition and uniqueness. Yet, often this incredible culture becomes entangled with and overshadowed by the polemical history of the terrorist group, ETA. CLC columnist Freya John seeks to explore the beauty of the Basque country, to show that although it has been associated with terrorism in the past, there is so much more to the Basque country than its turbulent history.

If you venture to the point where Northern Spain meets Southern France, you might find yourself lucky enough to step foot in a place known for its fiery and impassioned desire for independence and its extraordinary culture. The Basque Country, or euskal herria, as it is known in their fascinating language, is probably yet lamentably best known for the terrorism of the independence seekers ETA, who were predominantly active during the 20th century. However, the magnificence and strength of its unique culture and rich tradition should not be overshadowed by the turbulence of a terrorist organisation. Starting with language, I will explore and share the various cultural intricacies which, over time, have woven together to create the beautiful tapestry that is Basque identity.

The Basque language, known as Euskera for many linguists, is the biggest mystery in linguistic history. It is this intense sense of enigma that has, throughout history, played a crucial role in preserving the fascinating notion of Basqueness, having survived the conquering pressures of the Roman Empire. For years, even the most elite and esteemed linguists and scholars have been left blindsided by the mystery of Euskera, as if it were an unruly plot dreamt up by a master criminal. But what exactly makes this language so mysterious?

Unlike other European languages, Euskera does not occupy a place on the Indo-European language tree, bearing little to no similarities with any other languages. Its origins, therefore, are the ultimate linguistic mystery. You might suppose that the Basque language would look and sound relatively like Spanish, given the Basque country’s geographical whereabouts. Yet, this couldn’t be further from the truth. The Basque country spans the Western Pyrenees, across the Spanish-French border, which suggests that you might be able to see some Basque influence on French and Spanish, or even vice versa, you might expect to see the influences that the Romance languages have potentially had on Basque over the centuries. The Basque Country comprises two Spanish Autonomous Communities (the Basque Country and Navarre) and three French provinces (Lower Navarre, Labourd and Soule). However, Euskera has preserved its own individual charm despite being surrounded by Romantic influence.

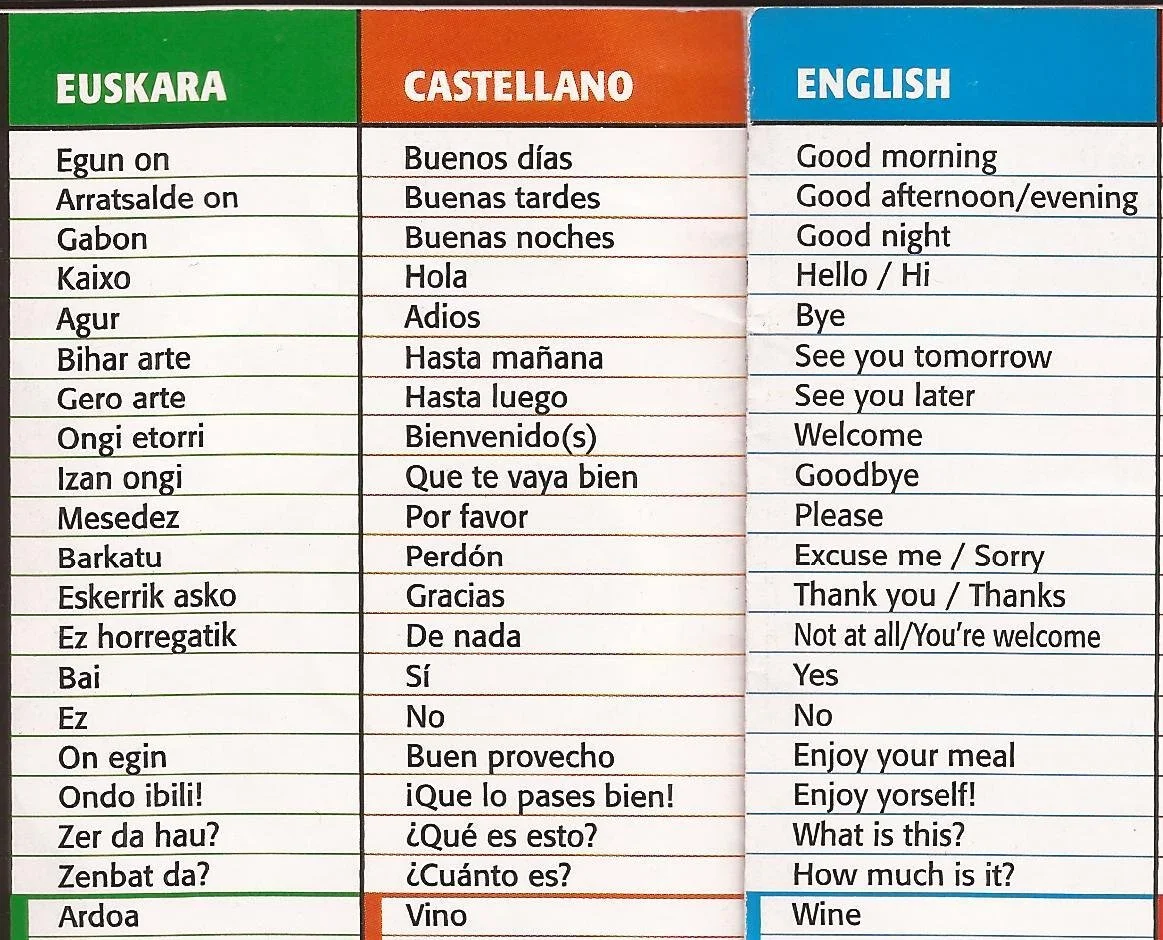

*Description of the chart: The chart shows the staggering differences between English, Castilian Spanish and Euskera. As we can identify, there are, interestingly, no similarities between Spanish and Euskera, reflecting just how unique it is, despite the Basque Country’s location.

This chart outlines only a fraction of the uniqueness of this special language, its complete individuality rendering it a complete mystery. Fascinatingly, its phonemes and sounds (such as the combination of the consonants ‘tx’ which is pronounced ‘ch’) make it doubly difficult for Spanish speakers, further distancing it from its neighbours in Spain. Linguists have toiled over finding its origins, but their efforts have consistently been made to no avail.

Yet, what these linguists have found incredibly remarkable is Euskera’s survival over the years, having withstood major influence of the Roman Empire, an authority that various other languages failed to survive, not to mention Franco’s abolition of all regional languages in 1939. Its linguistic endurance has interestingly been attributed to the Basque Country’s geography. The idyllic landscapes of San Sebastian and Bilbao are not just beauties to be marvelled at, but rather something vital to the preservation of Europe’s oldest and most mysterious language. Scholars have deciphered that the Roman Empire conquered the cities of the Basque Country, meaning that those who lived in the Basque mountains were safe from any influence of Latin, in turn, allowing the language to escape Latin’s devious clutches and unquestionable, unwavering influence on the shaping of language in Europe.

Over the years, Euskera has not been protected from adversity, with Franco desperate to abolish any uniqueness that he considered compromised his despotic regime, meaning that in 1939, Euskera was forced to become nothing more than clandestine whispers in family homes. This type of linguistic plight is not uncommon. Languages and their survival have often been threatened throughout history. It is always interesting to contemplate something close to home, to draw similarities between British and European predicaments. The struggles of the Basque people are potentially comparable with those of the Welsh, who have also suffered a similar type of linguistic oppression. As with the Basques, this demonstrated the importance of language to cultural identity. Welsh was banned by Henry VIII in 1536 and it was not until the late 1800s that the teaching of it began to reemerge in schools. Following the Welsh devolution referendum in 1997, where a degree of self-government was proposed, which can be likened to the autonomy acquired by the Basques in 1978, there was a real resurgence of the Welsh language. The development of Welsh post referendum ultimately reflects how language is a key and integral proponent in establishing national identity. When all road signs in Wales started to be written in both Welsh and English, and schools started to become completely Welsh speaking, Wales seemed to become more Welsh. In much the same way, the Basque country started to become more Basque after the reinstatement of their incredible language after Franco’s regime came to its end.

Euskera has grown significantly in popularity, offering and hinting at a positive future for the development and diffusion of Euskera, and therefore the distribution of Basque culture across the world. The success of Euskera in recent years can be partly attributed to modern day advances such as the establishment of Basque language only television networks, the three main being ETB1, ETB3 and Hamaika Telebistadd. More than 70% of people under the age of 25 in the Basque Country are now also able to speak Euskera, a remarkable increase from a quarter 25 years ago. The Basque identity is evidently being preserved through the distribution and teaching of this mysterious language, without which, the Basques would not have had such a fascinating historical struggle or the cultural diversity that they have today.

Without the language, there would have been no need to fight for the preservation of identity because Euskera differentiates the Basques from their Castilian neighbours. It is likely that the patriotic flame of the Basques will never be extinguished, they will never lose this fascinating ‘dream-like quality’, that Mark Kurlansky, author of The Basque History of the World has written so extensively about, all thanks to their incredible, unique language.