Cairo Chronicles IV: The Desert Dichotomy

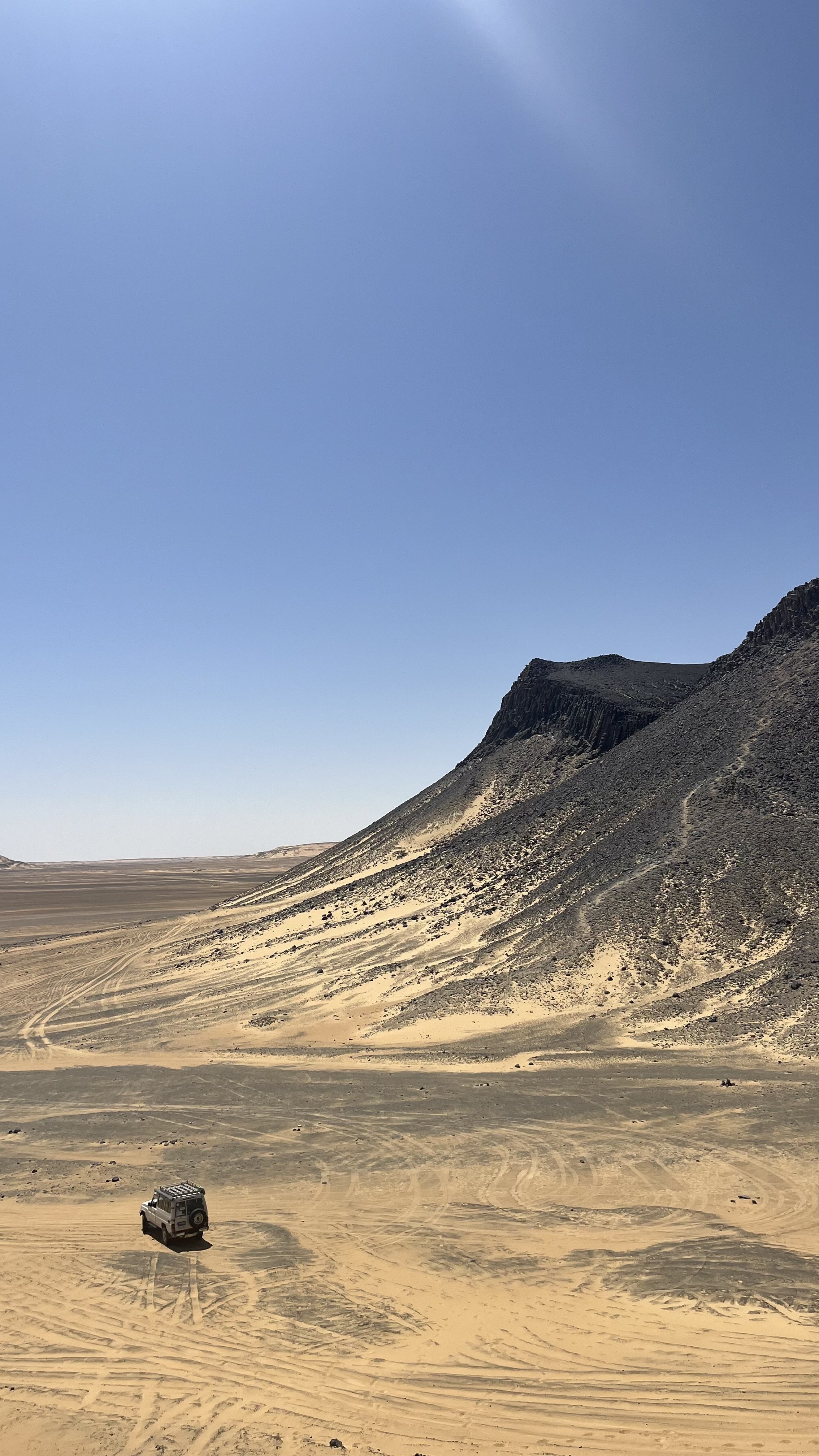

The vast emptiness of the Egyptian desert. Photo: Daisy Wright with permission for the CLC.

Egypt is a dry, sandy country, approximately 96% of the entire country is desert. This dichotomy between fertile and arid lands has characterised much of the country’s long history, with the areas along the Nile being the lifeline of Egyptian civilization. These were the only areas of land that could be cultivated, and so even up to today it is these lands that sustain 99% of Egypt’s huge population. However, as Egypt moves forwards it seems that its politicians and leaders see the future of their country in the desert.

The desert in Egypt is not one homogenous area: many of the areas in Upper Egypt have a strong culture from the Nubian people who inhabit them, indigenous to the area in the south of the country and northern areas of Sudan. They differ culturally and ethnically from much of Lower Egypt as their heritage comes from the original settlers of the area, way before the arrival of the Arab tribes. This was taken advantage of by Egypt in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, employing Nubian people as code-talkers as they have a language not widely known that could be used for transmitting secret information. However, resettlement of the Nubian people has affected their traditions, particularly since the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the sixties, bringing them into contact with a much more urbanised way of life. Lower Egypt has seen a similar process too: traditionally the arid climate outside of the Nile Delta has only been able to sustain the most foolhardy of nomadic Bedouin groups. Yet the changing climate and spreading of development into the desert is changing their traditional way of life.

As the unrest in Egypt of 2011 fades into distant memory, more and more travellers are adding Egypt to their list. However, the Bedouin people are being affected by the Egyptian government’s pushes towards infrastructural developments and urbanisation. Take Sharm el-Sheikh for example: a teeming resort town enjoyed by many western tourists, with development exploding in recent years as tourists return in increasing numbers to enjoy what it has to offer. Western influence from the tourists in Sharm threatens their traditional values and practices: not only have they begun to marry outside of their tribes, a practice frowned upon not that long ago, but they have also been dispossessed of many of their lands to be replaced by the construction of huge resort hotels. This boom in tourism doesn’t always help the Bedouins, instead they are further affected by unemployment and a loss in their traditional identity.

This isn’t only happening in Sinai; desert reclamation in Egypt manifests as the construction of shiny new satellite cities in the areas surrounding Cairo. Despite being built in the dry desert, these new cities are full of green spaces, sprawling malls and gated communities - the very picture of an American suburb. Many of these new satellite cities rely on vast quantities of water to keep the green spaces looking green. For the country that hosted COP27 last year, this seems like a huge misuse of finite water resources. Given that many of these areas are inhabited by the higher strata of society, it renders water a commodity of the rich, leaving dusty downtown without this kind of excess and luxury.

Initially designed to alleviate the housing problems faced by many of the poorer areas of Cairo society and reduce the overpopulation burden, they have become the opposite: a haven for a new generation of Cairene. The first satellite city was established in the 1960s by Nasser in the wake of the 1952 Revolution: Nasr City was intended as a new capital to represent Egypt’s shiny post-Colonial future, with alternative administrative buildings and modern housing. This housing was meant to be affordable as it was the lower strata of Egyptian society who desperately needed places to live. Yet, this is not what happened, a trend which marks these satellite cities.

Sadat’s ‘Open Door Policy’ embraced the pursuit of these kinds of projects. It attempted to encourage foreign investment and boost urban growth in these desert areas rather than enacting any further development in Cairo itself. Instead, they have done little to reduce the overpopulation burden, and just extended Greater Cairo further. Only the richer sectors of society and expats can afford them as they are only connected to the rest of Egypt by huge highways; a car is needed to live in these cities. Although plans exist to connect them with public transport, these developments are only in their very early stages and will not be completed before prices of these areas skyrocket further.

These new areas also seem to represent the future of Egypt, with urban modern metropoli multiplying in the desert, almost like an Egyptian replica of Dubai and Saudi Arabia. One of these new cities is even called New Cairo, suggesting that ‘Old’ Cairo is not where the future lies for Egypt. It is as if culture is not what will be valued in the future. Rather, new developments, huge malls and real estate investments are what will resolve Egypt’s current financial issues.

In 2015, the Egyptian government announced its plans to construct the New Administrative Capital in an attempt to render Cairo defunct in any institutional or official sense by moving Egypt’s parliament, presidential palaces, government ministries and foreign embassies to this new urban development. It also aims to reduce congestion in Cairo itself, transferring governmental and official jobs there, which will help to encourage people to move out to new housing. However, this all comes with a hefty price tag, and when Egypt is facing a financial crisis, it begs the question: where is this money coming from?

Originally, an Emirati construction company, Capital City Partners, was to take on the task of building this new metropolis. However, barely 6 months after this had been proposed it was announced that a new company had taken up the reins on the construction of this project: China State Construction Engineering Corporation. Egypt seems to be another country embraced by China in its ‘Belt and Road’ initiative in which it pursues its interests by investing overseas. However, this is a double-edged sword as it allows China to use its economic strength to increase its influence in Egyptian territory.

There is no doubt that Egypt’s landscape is changing, with traditional lifestyles being endangered as this mass project of urbanisation is underway. The financing of the developments by China seems a far cry from what Nasser started with the first satellite city and drawing Egypt away from its historical pursuit of Pan-Arabism. Is that the kind of future that Egyptians want? Financed by China and only for the rich?