Germanistik II: In search of the female writer… along the shelves of the bookshop

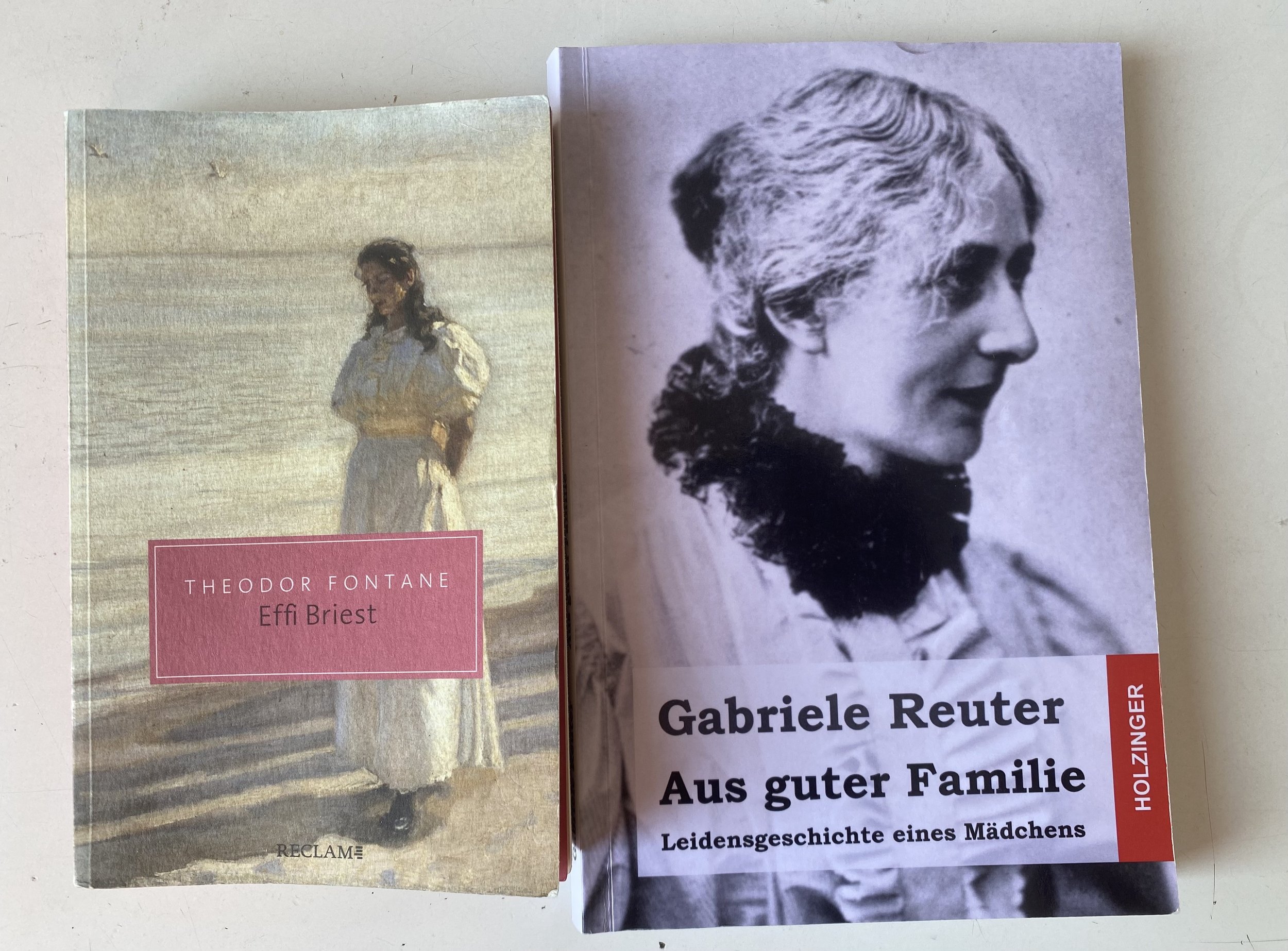

Effi Briest and Aus guter Familie side by side. All images belong to Author.

In this column, Maddie Hazelden reflects on her experience of studying Germanistik while on her year abroad and the lack of female representation she found there. The series will explore reasons behind the dearth of women in the German canon by delving back into literary history and bringing attention to those female writers whose names have been reduced to footnotes.

A few weeks ago, I was in Thalia, the Waterstones of Germany, just browsing before I went to collect a terribly exciting grammar book I had recently ordered. The Bonn store is located in an old theatre with books lining the wings and plush reading chairs looking out over where the stage used to be. I passed by the classics section – the usual suspects were there of course: Goethe, Schiller, Thomas Mann, Bertold Brecht and so on. While I was scanning the shelves, my eye was caught by a copy of Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest with a beautiful water-colour of the eponymous protagonist looking out over the sea mist on the front cover. This German Realist classic is often compared to Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina for its depiction of an unhappy marriage and the fallout of its female protagonist’s affair.

I was reminded of a book that was also published in Germany in 1895, Gabriele Reuter’s Aus guter Familie. This novel made Reuter an overnight success when it was first published, sparking much debate among literary critics and feminist theorists alike in response to its unflinching depiction of a young woman, Agathe, who is gradually broken by the restraints placed on her intellect, desires and development by the Wilhelmine society of the late nineteenth century. Despite the waves this novel created in the German literary landscape at the time, I have not yet come across Reuter’s work in a mainstream bookshop in Germany. I tracked down my copy online from a site selling second-hand copies. As can be seen in the image at the top of this article, there is a stark contrast between the front covers of the two novels, one that says a lot about their treatment by literary history and the publishing industry.

Although Fontane wrote Effi Briest towards the end of his career, while Reuter was much younger when Aus guter Familie was published, they both received significant critical and commercial success. Both received praise from their contemporary, Thomas Mann and later on Reuter’s novel was picked up on by Freud, who was impressed by her keen observation and credited her with providing an insight into the origins of neurosis before psychoanalysis had been properly theorised. Aside from their success with critics and the public, the two novels also contain further similarities in their themes. They both critique the stuffy conventions of Wilhelmine society, a way of life which was on its way out by the end of the nineteenth century, but they do so in different styles. Fontane’s novel is hailed on the one hand as a masterpiece of Poetic Realism, while Reuter, on the other, employs a grittier Naturalist approach to depict the harsh reality faced by unmarried women both among the bourgeoisie and the working classes of the time.

In this case, we are left to wonder why it is that one of these novels was granted access to the literary canon and the other was left to fall out of print until relatively recently. It is crucial to emphasise here that although both novels portray an indictment of the prevailing bourgeois morality of Wilhelmine Germany with female protagonists, only one was written by a woman. This allowed critics to cast Reuter under the derogatory label of Frauenliteratur, a term which was almost synonymous at the time with Trivialliteratur, and therefore could have no place in the canon. In their view, Fontane was writing about society, while Reuter was writing about women - not a worthy subject of serious literature.

It has to be said that Aus guter Familie is more radical than Effi Briest both in the themes it depicts and how Reuter depicts them. Although Fontane’s novel is a critique of society’s strict rules, it is only gently critical when compared to the sheer cruelty experienced by Agathe. While Effi does have moments of happiness, tonally Reuter’s novel is devastatingly bleak in its depiction of its protagonist’s emotional and intellectual starvation. Furthermore, at the end of the novel a certain amount of blame is apportioned to Effi for the breakdown of her marriage and subsequent expulsion from society. Following Agathe’s mental collapse in the final pages of Aus guter Familie, we are left in no doubt as to who is to blame for her fate - the suffocating milieu in which she was raised.

Published by the Fischer press, Aus guter Familie ran to twenty-eight editions from its year of publication until 1931, a number which Effi Briest did not reach in the same time period. However, Fontane had his writing compiled into a Gesammelte Werke (collected works) in a way that Reuter’s never was – despite her continuing to publish to acclaim after her initial success. This fact is pointed to by scholars Renate von Heydebrand and Simone Winko as a key explanation for why Effi Briest attained canonical status while Aus guter Familie was missed out. Another can be found in the treatment of the respective works under the Third Reich. Unsurprisingly a novel that criticised so severely a society which dictated the role of wife and mother for women at the expense of their emotional and intellectual development was not popular with the Nazis and it is no coincidence that this was the decade in which the novel fell out of print. Meanwhile, Fontane’s more gentle criticism could be interpreted as a moral lesson for society to respect the sanctity of marriage and a cautionary tale for women who might wish to transgress. In fact, the first film adaptation of Effi Briest, entitled Der Schritt vom Wege (A Step off the Path) was released in 1939, portraying Effi’s husband in a more sympathetic light.

After many decades in the wilderness, Aus guter Familie is now back in print thanks to the dedication of feminist academics who have worked hard to rehabilitate writing by women which has been lost over the years. There is also an English translation available by Lynne Tatlock. Having said this, the novel is still not widely known outside of academic circles and is nowhere near to recovering the fame it once held. However, I hope this will change as the work is gradually added to more school and university syllabuses. I hope also that someone will design the front cover it deserves.