Tbilisi’s Turning Point: Election Uncertainty in Georgia’s Capital

Courtesy of Maddy Guha

Before coming to Georgia, I was told to expect a general disdain for Russia and all things Russian. Anyone who has ever walked through a graffiti-ridden street in Tbilisi can testify to this, yet it’s not entirely replicated in the current political climate. Russia has found a role in Georgian society by acting as both a symbol of tradition and a looming threat. As the younger generation here, born after the USSR, generally share a strong anti-Russian sentiment, amongst older generations, it’s more of a mixed bag; which I had not expected. When I think of Russia through a Georgian lens, my mind immediately goes to recent events such as the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia, or attempts by the Soviet government in the 70s to repress the Georgian language - and these are only examples that I can name off the top of my head, the list goes on…

The ruling Georgian Dream party, run by an eccentric oligarch named Bidzina Ivanishvili, certainly rejects the “Russia bad” narrative. Ivanishvili, who made his fortune selling computers in Russia in the 90s has unfathomable levels of wealth in the eyes of most Georgians. So why wouldn’t he want to keep Georgia in alliance with Russia? Many people in Georgia vehemently disagree with everything Georgian Dream stands for, and do not view the Russian state as a reliable friend they can lean on. When Ivanishvili announced the Russian-style ‘Foreign Agents’ bill in Georgia earlier this year, protests occurred for weeks, as many citizens believed the law would not only inhibit their attempt to join the EU, but also stigmatise any companies that would be classed as ‘foreign agents’, as well as burden them with endless fees and administration. So all I could think about once I arrived in Georgia was who votes for a party that shills for Russia? And after speaking to various people, I feel I have more of a gauge on the situation.

Firstly, you cannot go anywhere in Georgia today without seeing Georgian Dream posters left right and centre. Even in quite isolated villages. Most of them look like this:

The one on the left appears all over motorways, tower blocks and public transport. From what I have been able to gather from Georgian speakers, it talks about entering Europe peacefully. This is honed in by the poster on its right, which reads: ‘No war! Choose peace’. A very sensitive image to be displaying across the whole country, it implies that if Georgia tries to move closer to the West, it will meet the same fate as Ukraine. This has been a deliberate threat used by Georgian Dream, to convince voters that there is no simple solution. Certain news companies have refused to broadcast these images, as they believe that they are a deeply unethical attempt at fearmongering. The sheer frequency of these messages feels rather heavy-handed, and as an outsider, I can see how this would leave such a mark on the population. One man who I felt as though had fallen very hard for these advertisements, was a taxi driver, who seemed to have a far more sympathetic view towards Russia than most, and claimed that Georgian Dream was pushing the country in the right direction in terms of development. He seemed to take more issue with the West and the ‘gay propaganda’ he believed that it distributed. Ultimately, he told us that there was no optimal outcome for the election this coming Saturday.

Poster depicts the opposition held on a leash and reads ‘No to war! No to agency!’

Another tactic that Georgian Dream seem to use was explained to us by a young journalist, who told us that the ruling party draws on more nefarious practices where it can; In the run-up to the election, Georgian Dream released many prisoners, based on a compact that they would both vote for them and beat up protesters at any anti-government rallies. On Wednesday, I stayed out of the city centre as there was a Georgian Dream rally - what I did not realise until later was that many of the attendees were not even from Tbilisi but had instead been bussed in from across the country, purely for the rally. Furthermore, the party seems to use some fairly people-pleasing policies in the final days before the elections. I remember a far more anti-Russia taxi driver, who could not fathom Brexit, showing us how the roads had recently been fixed as a quick attempt to snap up any last minute votes. This tactic was used far more harmfully in the controversial passing of a new ‘Anti-LGBT Propaganda’ law, which, in a vastly Orthodox-Christian country, has had a range of responses. For many young people, it reinforced all distaste towards Georgian Dream, especially as one of Georgia’s first transgender celebrities, Kesaria Abramidze, was tragically murdered in her own home the day after the bill passed.

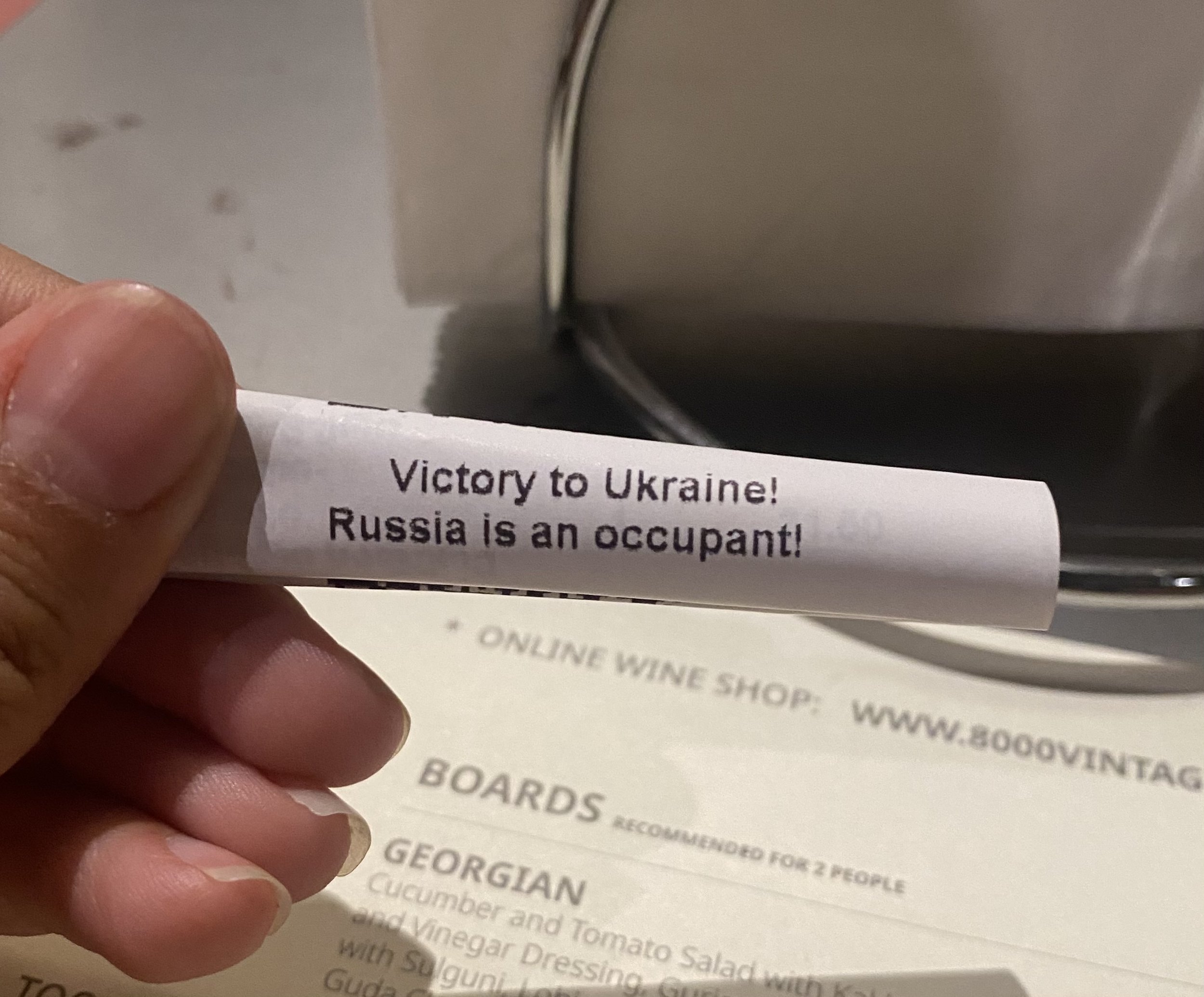

While the official advertisements seem to be overwhelmingly in favour of Georgian Dream, many people create their own acts of resistance. For example, I have now been to multiple restaurants with passwords such as ‘Abkhazia (currently occupied by Russia) is Georgia’, and also political messages on receipts or menus, such as this one in a wine bar in Tbilisi:

Pretty much whoever I have asked about the elections this coming Saturday and their predictions, has replied saying that they genuinely have no idea what could happen. The journalist we spoke to told us that although the general sentiment feels very anti-Ivanishvili, Georgian Dream simply cannot afford to lose this election; they have invested far too much money, and he strongly implied that a rigged election may be a possibility. While a younger man in a bar told me that he believes Georgian Dream will actually lose, I realised that there is truly no way of knowing until Saturday. While many people in the older generations feel a sense of nostalgia from the USSR and more sympathetic towards Russia and Georgian Dream, the highly passionate younger generation wishes for a chance to join the EU and step away from Russia. Whatever the outcome of the election on Saturday, disputes will arise, from the family dinner table to the city streets.

All images belong to the author, Maddy Guha