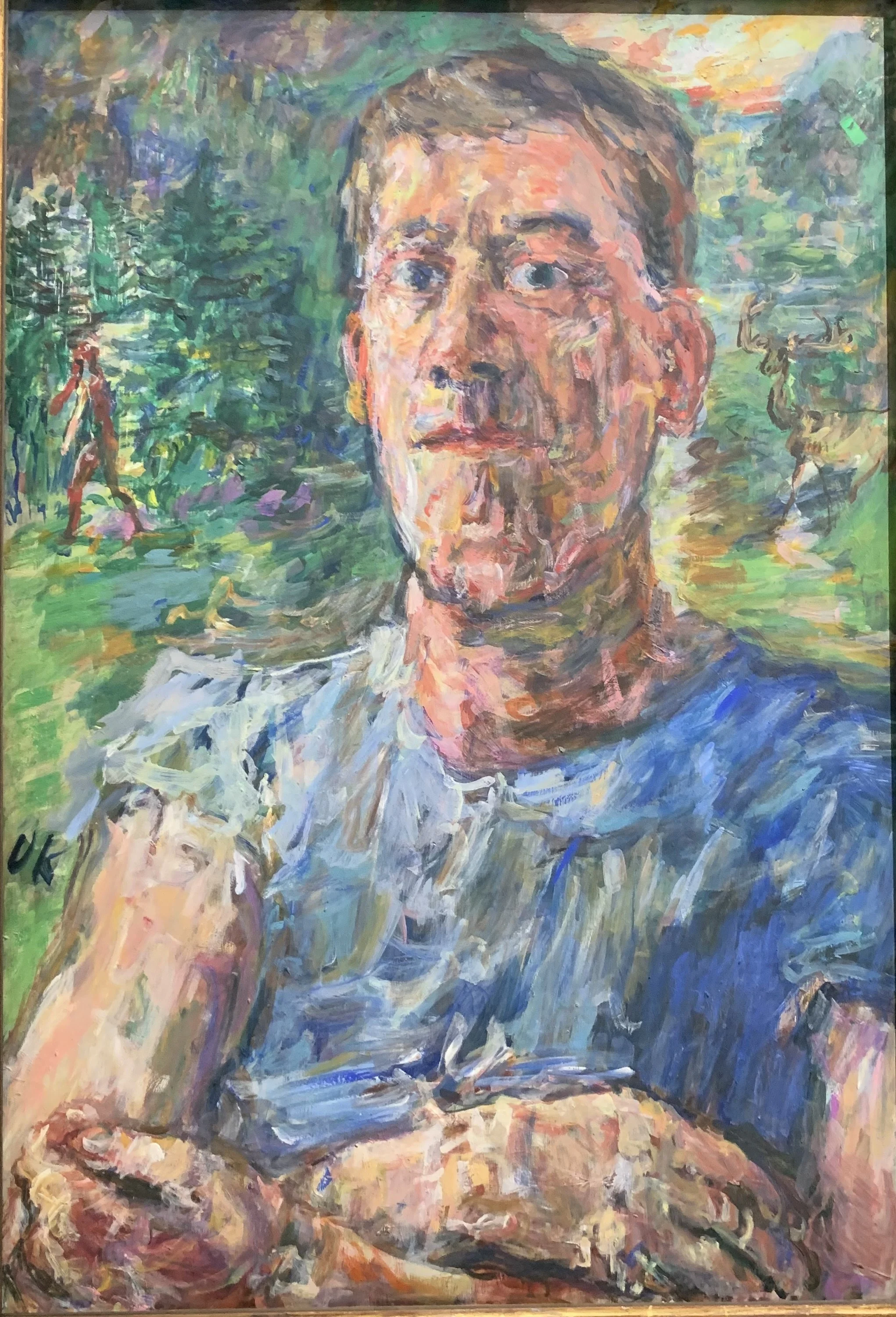

‘The ‘Aestheticisation of Politics’ - Oskar Kokoschka, a Degenerate Artist

‘Selbstbildnis eines ‘Entarteten Künstlers’ (Self Portrait of a Degenerate Artist), 1937 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

The ‘terrible child’ of Vienna

Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), the polemical poet, artist and playwright, is known as a prolific figure of the Viennese avant-garde and pioneer of the Expressionist movement. Despite working alongside his contemporaries, the Die Brüke and Neue Secession artists, Kokoschka never associated himself with a particular band and refused to classify his style, which evolved continually to the rhythm of changing society. As he saw it, his role was to enlighten the public, warning them of political and social menaces, or, more critically, to confront them with that which they wished to ignore.

Kokoschka’s style is hard to pin down. With some works characterised by subtle and detailed touch, and others by heavy-handed, distorting textures, painted on with his hands, Kokoschka’s work evades both stylistic classification, and criticism. This lexicon was adopted in the German National Socialist Cultural Policy in the 1937-8 travelling exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). Stephanie Barron comments upon the German Entartet, a biological term depicting the non-belonging of certain organisms to their species. It is precisely this lack of classification that, whist viewed by Kokoschka as representing free, engaged creation, formed the basis of the Nazi’s critique of this work.

Degenerate Art: the looting of modern art in Germany

Schandausstellungen (exhibitions of shame) became the poster medium for the barbaric destruction of modern art by the National Socialists, a style deemed synonymous with Jewish or Bolshevik art. However, the defamation applied not only to Jewish artists, but also to any expressionists, cubists, dadaists, surrealists, symbolists, and post-impressionists. The list is exhaustive.

It is seemingly easy to note what Degenerate art was not, but quite hard to define what it was. This is not only due to the disorganised nature of Nazi discrimination, merged with anti-Semitic, anti-communist propaganda, but also to inconsistencies within the party, notably between Alfred Rosenberg (cultural leader of the Reich from 1934) and Joseph Goebbels (Reich Minister of Propaganda 1933-1945) regarding the artistically acceptable.

By and large, Nazi artistic ideals corresponded with the writings of ideologist Paul Schultze-Naumburg. In his books, Die Kunst der Deutschen (Art of the Germans), and Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race), Schultze-Naumburg alludes to ‘racially pure’ artists, those able to produce ‘healthy art’. Indeed, images of health and sickness were often used by the Nazis to distinguish between sickly, abominable modernism, and healthy, idealistic classicism.

The attempt to purify art began with the late 19th Century German ethno-nationalist Völkisch movement, hailing the singularity of German production, and works fitting this mould were exhibited against Degenerate Art in the parallel Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition). Despite Adolf Ziegler’s statement in the opening of the Degenerate Art exhibition, “German ‘Volk’, come and judge for yourselves!”, fair judgement was impossible. With works carelessly hung, erroneous descriptions scrawled on the walls, and the presentation of opposing, exemplar art, judgement had been pre-inscribed.

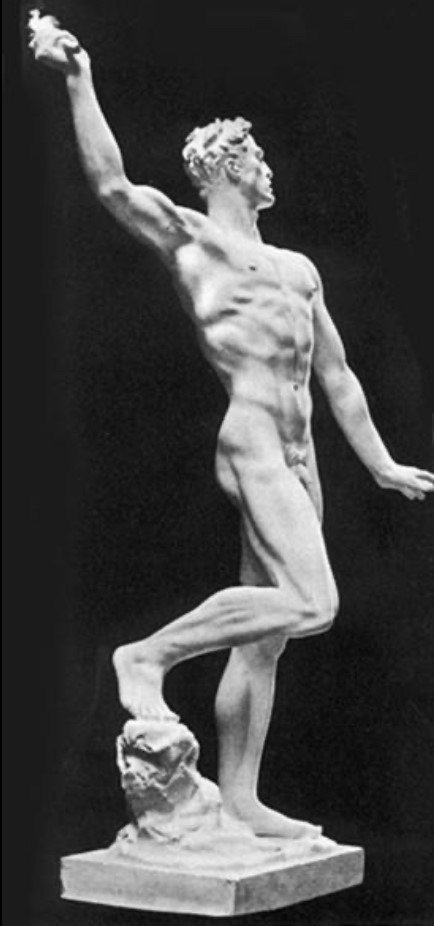

With the forced exile of Germany’s leading artists, amongst whom were Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Kokoschka, artists such as Arno Breker were endorsed as the antithesis to the degenerates. Breker’s sculpture, Prometheus (1935), displaying a chiselled, athletic male nude is clearly reminiscent of classical Greek sculpture. It was this image, connoting strength, and glory, that the National Socialists wished to recreate as their own.

Prometheus, 1935 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Kokoschka, the unpatriotic degenerate

Standing in stark contrast to the muscular figures of the celebrated neo-classical works, are Kokoschka’s portraits. Admittedly, they are largely not what you might call aesthetically pleasing. However, pleasing the public was never the artist’s intention, but rather searching beyond and beneath appearances, for the depth of human expression, bringing to light the deficiencies and anxieties of humanity. Glancing at Kokoschka’s 1909 portrait, Vater Hirsch, exhibited as degenerate in Munich, the subject’s false teeth attract our gaze. Rather than avoiding portrayals of imperfection, the expressionist draws special attention to it. Moreover, the thick, impasto painting technique, clearly drawn from the post-Impressionists contrasts with the clean strokes of the classicists. Tension and discomfort are quite literally held within the paint itself.

Vater Hirsch, 1909 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Embracing such tensions, Kokoschka’s attempts to represent unvarnished expression hint at Surrealist elements. His paintings of nature negate depictions of beautiful German landscapes endorsed by the authorities. Dolomitenlandschaft Tre Croci (1913), and Alpenlandschaft bei Mürren (1912), both capture a sense of irreality, be it through the unnatural colour of the blue-tinted horse, and purple mountains, or the blurred outline of the landscapes and the rippling sun. Such paintings that refuted modes of understanding entered the host of works pertaining to what Goebbels called the decadent and anti-nationalist ‘era of decay’.

Dolomitenlandschaft Tre Croci, 1913 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Alpenlandschaft bei Mürren, 1912 (Photo:Einav Grushka)

Reflexive Art

The image of art propagated by the Nazis was one that aimed to unify German life and legacy with the glorified ancient world. Kokoschka’s art, however, is self-aware, reflective of its own falsity and conscient of its imperfection. A work that epitomises this is Der Maler II (Maler und Modell II) (1923), a rare example of a double self-portrait, the artist being both painter and model. On both ‘canvases’, the tonally unified backgrounds (green and red) are quixotic, and the block use of primary colours is almost mocking, sarcastic in its simplicity. Here, Kokoschka makes not the slightest attempt to resemble reality, emphasising painting as a RE-presentation, as falsified copy.

Der Maler II (Maler und Modell II), 1923 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

Thus, evidently, Kokoschka avoids realism in his works. The amalgam of unnatural colours, and erratic, unbalanced brush strokes in Die Freunde (1917-18) would render the unfolding scene unrecognisable, were it not for the vague black outline of the figures. As you approach the frame, the work loses shape, the scene melting into a mess of colour and shape, yet standing back, the intricacy of the work is rather astounding. The ‘reality’ depicted is thus fleeting, and like Kokoschka’s style, is evolving, vivid in its fluidity and movement. Despite no hints of classical perfection, there lies a mastery which exposes a new beauty, divorced from the ancients.

Die Freunde, 1917-8 (Photo: Einav Grushka)

A degeneration of expression

The title for this article was taken from Walter Benjamin’s depiction of Fascism as, ‘die Ästhetisierung der Politik’ (The Aestheticisation of Politics), and Kokoschka’s deliberate mocking of aestheticisation contributes to our understanding of his work. Ironically, the aestheticization of politics is perhaps secondary to the policing of aesthetics, a devastating process that not only exiled the great artists of Germany, and demonised promising Jewish artists, but also unsettled the natural progression of art along the social timeline. What it truly was - a gross distortion of art history, a degeneration of expression.